If you follow the online chatter about Book Apps, you soon notice that it comes largely from tech companies and conference organisers. The voice of publishers can also be heard, occassionally, but writers (and to be specific, writers of non-childrens fiction) are noticeably quiet.

Writers, by and large, and not slow to spot opportunities, so I’ve been talking to a lot of them to understand their relative lack of interest in experimenting with this emerging form. What follows is not a representative sample of authors, of course, and I’m about to generalise wildly when I merge all those different conversations into the following statement. That said, the general concern was this:

If they can’t sell what they write on Kindle, then it’s not worth their time writing it.

Or in other words, iPads and Kindle Fires and forthcoming Windows tablets are all well and good, but the Kindle doesn’t support .epub3 so there’s no point playing around with the potential that offers. There was more to it than that, of course – there was the expected creative concern about the nature of interactive fiction, if not the desire to engage with the problem. There was interest in the idea that some developers may actually have some money which they have yet to burn through. But more prominently, there was a desire for readers, and in particular the hardcore readers who read, buy, and talk about books a lot.

One claim that published and self-published writers alike make is that publishers currently have zero interest in building the careers of writers (which is odd, as this is exactly how publishers will succeed in the future). As a result, even established authors see indie and self publishing forming at least a part of their future. There ia a growing understanding that, despite iPads and Kobo and the like, the only ebooks which actually sell are Kindle. So, if they couldn’t put it out on Kindle and reach the existing, installed base of Kindle ereaders, then it wasn’t for them.

All of which begs the question of what interactivity you can currently bring to a Kindle, and the answer is very little. You can link through to different parts of the text, but you can’t use tracking variables or make decisions about where to go based on the reader’s past choices. Hacking your way around such limitations can allow you to be quite creative, however (and indeed the writer Richard Blandford and myself have worked out a very cunning way to publish his random short story collection The Shuffle on Kindle.)

Another writer who has engaged with these limitations is Caroline Smailes. Her eBook 99 Reasons Why tells the story of troubled 22 year old in the North East (one of those literary characters that stick in your head long after you finish the book). It also offers 11 different endings. When the story reaches its conclusion it presents the reader with a quiz to select the ending that they’ll receive. The quiz aspect is faked on the Kindle by repeating a few pages with different links, giving varying routes through what appears to the reader to just be three simple questions.

Another writer who has engaged with these limitations is Caroline Smailes. Her eBook 99 Reasons Why tells the story of troubled 22 year old in the North East (one of those literary characters that stick in your head long after you finish the book). It also offers 11 different endings. When the story reaches its conclusion it presents the reader with a quiz to select the ending that they’ll receive. The quiz aspect is faked on the Kindle by repeating a few pages with different links, giving varying routes through what appears to the reader to just be three simple questions.

The different endings are not just different because of the events that they describe, but they also differ by revealing new facts about the characters, meaning that the whole of the story is changed by the ending that the reader makes – it’s as if some film goers saw a film that reveals Darth Vader is Luke Skywalker’s dad, whereas others see a film that says Obi Wan is his father. This works thematically because Smailes’ main character is defined by her ignorance about the truth of her life and of her family situation.

The differing endings of 99 Reasons Why is an interesting experiment which I’d highly recommend (it’s well worth the £2.99 price), and one that gained the author a lot of publicity (always a good thing), but it is not something that would necessarily work with other stories.

Why can’t Kindle do anything more advanced? Here’s the thing – it can, but not in the UK. A development kit called Kindle Active Content will allow your Kindle to all the clever stuff you need to produce interactive fictions similar to Frankenstein on the iPad. More importantly, it is back compatible to all but the very first Kindle model, meaning that you could sell these things to the existing installed base of eReaders – the one thing that seemed to be the deal-breaker for all the writers I spoke to.

It’s sounds great, it sounds ideal – but for some reason it is US only. US readers can read/play involved Choose Your Own Adventure-type books, such as Warlock Of Firetop Mountain (ah, that takes me back…)And if it can run something like that, then the possibilities for more narrative-based experiments are pretty huge.

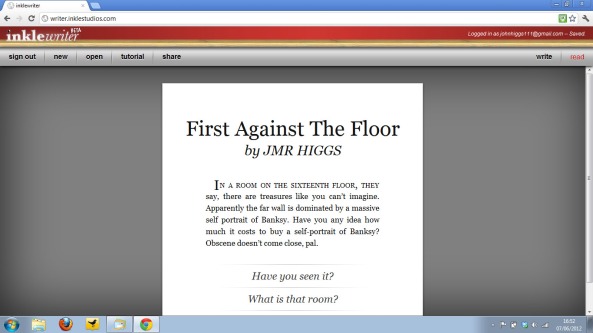

There does not appear to be any announced date or even a commitment to bring Kindle Active Content out to the rest of the world, however. It may well prove to be one of those baffling Amazon decisions, such as their refusal to release the Kindle Fire over here. All of which is a shame, because it is exactly the thing that writers I’ve spoken to are asking for. It is easy to see how something like the Inklewriter system would then be able to work for Kindle.

If Amazon get their act together, then we could see some really groundbeaking stuff start to appear. As seems to be the norm these days, however, the ball’s in Amazon’s court.